RICHARD SHARUM

All rights reserved © Richard Sharum

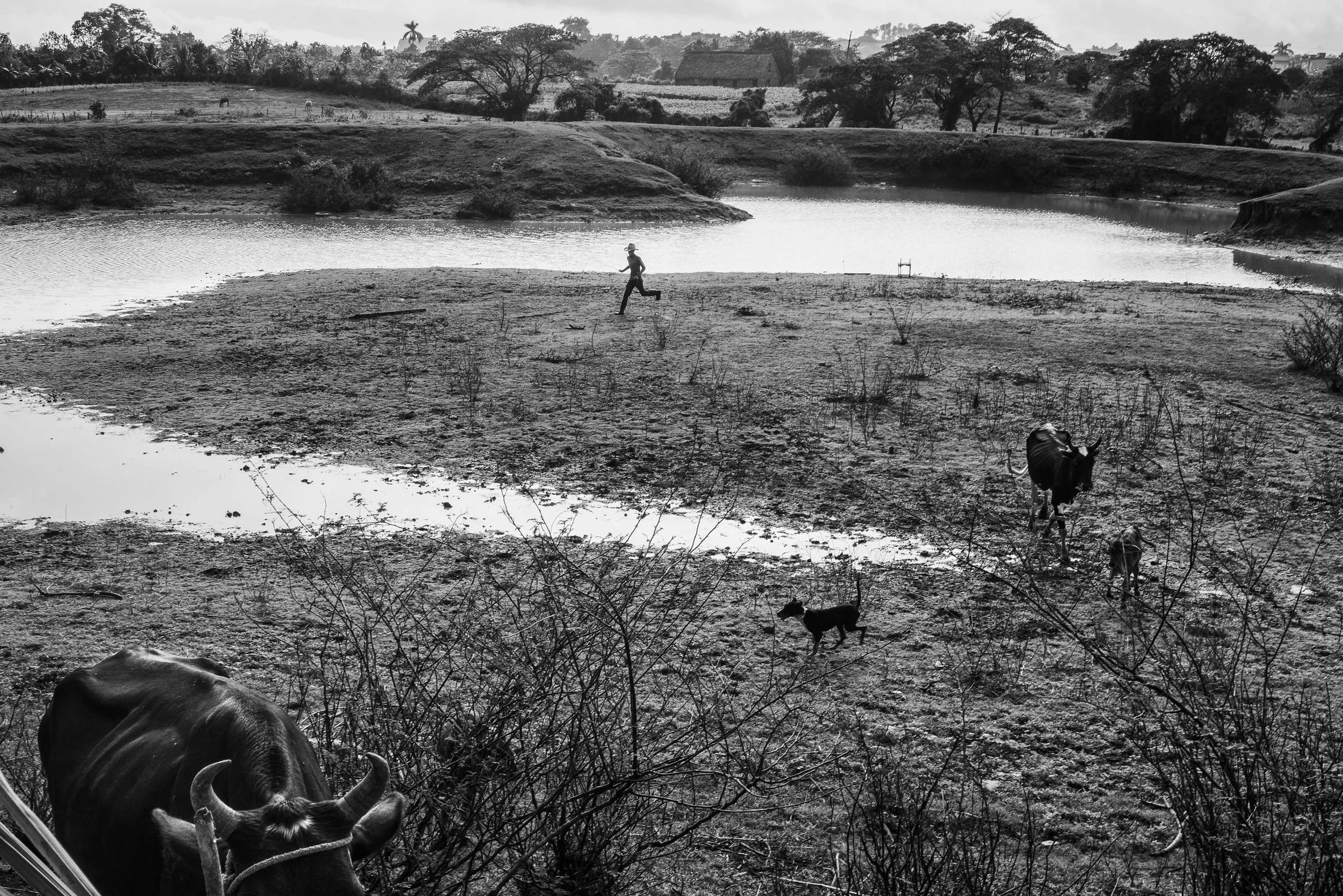

Richard Sharum is an American photographer whose work explores identity, conflict, and the emotional ties between people and place. Known for his intimate black-and-white images and long-form projects such as Campesino Cuba, his photographs blend documentary observation with a poetic sensibility. Sharum’s work has been exhibited internationally, establishing him as a distinct voice in contemporary photography.

When you first arrived in Cuba, what sensory experience — a sound, a smell, a rhythm — stayed with you and shaped the way you began photographing?

RS: The first thing I remember stepping onto the tarmac in Havana was the humidity, even in January, and all the palm trees on the horizon. I went west first, towards the tobacco fields. I was invited on horseback while there, and we ventured into the Valle de Silencio, a magical place. It was mystical in feeling, a light drizzle, and fields and fields of tobacco surrounded by the greenest mountains you have ever seen. The farmers who worked there had a small cabin, full of wood smoke from the cooking fire in the kitchen. There were kittens running around. I felt like I had been transported to another planet; it was so beautiful. That set the tone for the entire book, and I think people can sense that when they see it.

“The first thing I remember stepping onto the tarmac in Havana was the humidity, even in January, and all the palm trees on the horizon. I went west first, towards the tobacco fields. I was invited on horseback while there, and we ventured into the Valle de Silencio, a magical place”

The project feels guided by observation rather than narration. How do you decide when to intervene as a photographer and when to simply witness?

RS: I feel all my work is guided by observation, with the narration coming later, or subconsciously. Coupled with the observation though, there is always a feeling that prompts me to photograph. The moment is instantaneous. It is very rare that I “wait” for an image. It is akin to being drawn by a moment’s inherent magnetism. I feel compelled, almost without will, at hitting the shutter- like it is a last act of desperation, so as not to succumb too much to it all. The shutter is a pressure-relief valve of too much life.

“I feel all my work is guided by observation, with the narration coming later, or subconsciously”

There’s a strong sense of dignity in the way you portray people who live with very little. How do you balance empathy with distance when working in such environments?

RS: Well I grew up in an environment where people had nothing but their character. Material wealth was not a thing I experienced until I was much older, really in only the last 10 or so years. So seeing people survive from the salt of their sweat felt like home, in spirit, even though the environment was different. Also, I learned from experience that the only way to truly photograph from the heart, you must be as close to others as possible. All of the solutions to our problems as a society, I feel, lie in the spaces between us. It is my job as a photographer to explore these spaces, and come back with what I’ve found, for those too afraid to do the same.

“Well I grew up in an environment where people had nothing but their character. Material wealth was not a thing I experienced until I was much older, really in only the last 10 or so years. So seeing people survive from the salt of their sweat felt like home, in spirit, even though the environment was different”

Campesino Cuba seems to exist between documentary and poetry. Do you believe photography can transcend the documentary role, and if so, how?

RS: Only if done carefully. I feel photography is poetry, while also containing the latent power of a hammer, in the right hands. It is always the most difficult task, in finding oneself through an expressive medium, to be able to balance that sense of poetry with incidents recorded, as they are unfolding in real time. I don’t know if I will ever reach this level of enlightenment, but I will always work towards that.

Were there moments when the camera felt like a limitation — when what you were experiencing couldn’t be translated into an image?

RS: Of course. Sometimes, it was all too much, and I had to remind myself to put the camera down and just enjoy the moment, to get out from behind the camera. Life is for living. Photography, in the final form of photographic prints, is merely a physical receipt to that living and experiencing– showing you were there and as connected as possible.

The rural landscape in your work feels spiritual, almost sacred. How do you relate to the idea of faith or transcendence in your practice?

RS: I feel all transcendence we experience as humans is a direct result of the connection between all living things. It is merely tapping into that connection. Photography allows me, and has the potential to allow all, the ability to tap into that connection in a way that compresses time as we experience it. Life moves too fast for us to notice otherwise. In quantum mechanics there is a phenomenon known as “quantum entanglement”, whereas two forms of matter are connected by some mysterious force. If you separate the two particles, no matter the distance, and affect one, it will affect the other through some unknown connection. I believe it is the same with humans and all life. Photography allows me to search for it, and try to document that unspoken truth between all of us.

“I feel photography is poetry, while also containing the latent power of a hammer, in the right hands. It is always the most difficult task, in finding oneself through an expressive medium, to be able to balance that sense of poetry with incidents recorded, as they are unfolding in real time”

You’ve spoken before about humility in the creative process. What did Campesino Cuba teach you about your own limits as an observer?

I feel humility is too often mistaken for passivity. On the contrary, Campesino taught me how many limits I already had, as an individual and especially as a photographer. It taught me how to transcend those limits, and that maybe, as far as how we treat each other as a species, maybe we impose too many limits on ourselves when it comes to one another. Once again, I feel that the problems lie in the spaces in-between. I call for a revolution in the standard– thinking that we need more space between us. I call for the complete opposite.

“I will return and see my campesino families once again. In a way, it will feel like I am going home”

Now that the project has been exhibited and published, do you see it differently — has the meaning evolved for you with distance and time?

RS: Not really. I only miss all of those who I was close with while there and can no longer see. Maybe when restrictions ease again and they open flights back up to the eastern part of the island, I will return and see my campesino families once again. In a way, it will feel like I am going home.

All rights reserved © Richard Sharum