TATIANA ARISTIZÁBAL

All rights reserved © TATIANA ARISTIZÁBAL

Tatiana Aristizábal Zuluaga is a Colombian artist and photographer who delves into the relationship between territory and identity. Through her work, Tatiana explores memory, resilience, and the fragility of the environment, inviting viewers to reflect on how the landscapes we inhabit shape who we are. Her work blends poetic sensitivity with a critical gaze, revealing invisible stories that connect people, places, and memories.

Tatiana, do you remember the first moment or image that led you to write El caballero del páramo? Was there a scene, a place, or a person that sparked the initial idea?

TA: El Caballero del Páramo was born out of a need to speak about the environmental crisis in the Colombian páramos—very fragile ecosystems and water factories that are under threat from extractivism, large-scale cattle ranching, and climate change.

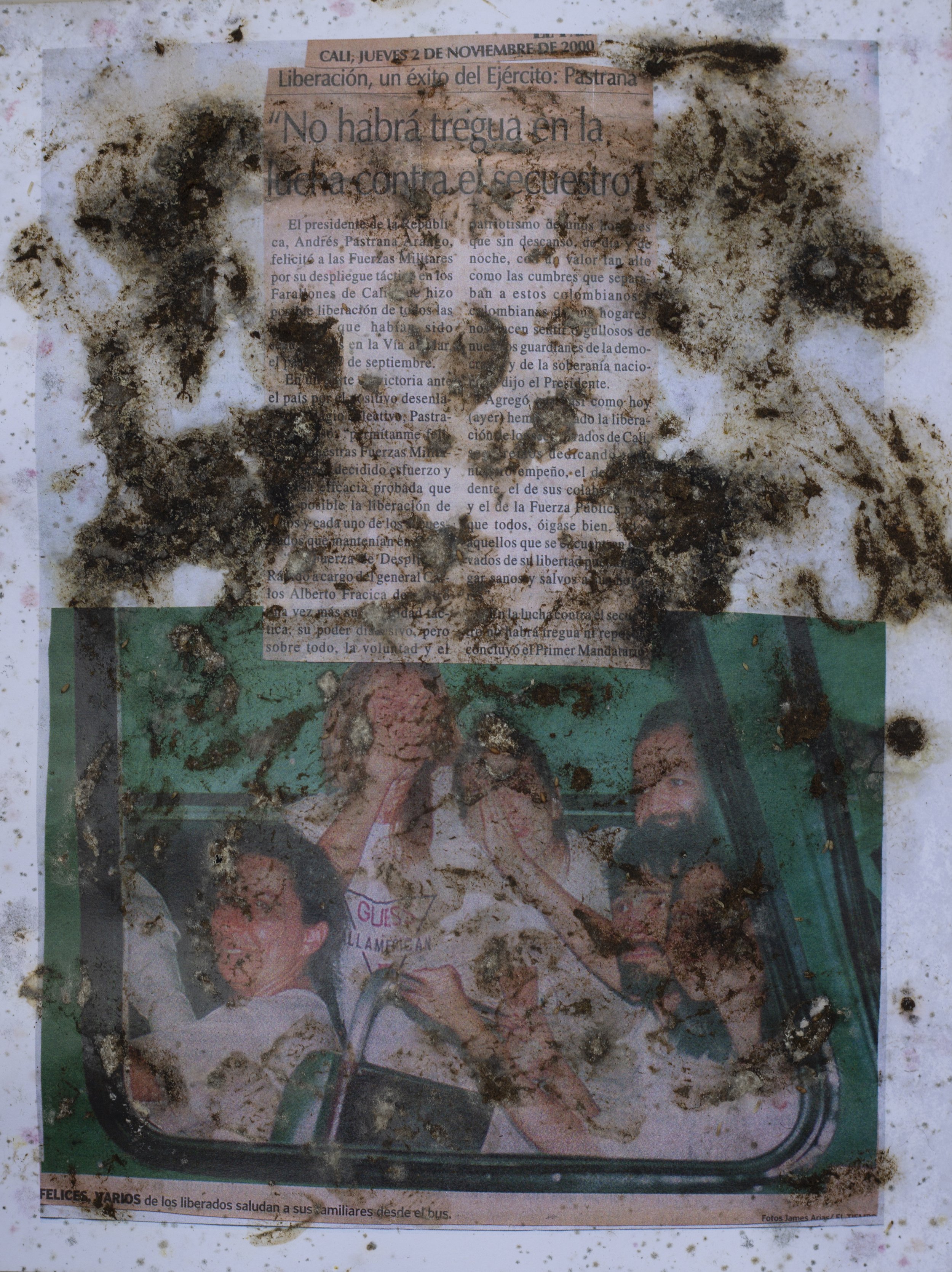

My brother traveled through páramos during his kidnapping, and I, coincidentally, visited one for the first time in an attempt to reconnect with the Colombian territory. When I told this to Carlos Tofiño, who helped me unravel this whole story, he immediately drew the connection between the páramos and the armed conflict. That’s when everything began to take shape.

“When I see a páramo, a frailejón, I feel the magic of the universe. How is it possible that a tiny plant can capture water from the air, and that this same water is what we drink in the cities?”

The páramo is a territory full of mystery and spirituality. What does that landscape mean to you, beyond being the setting of the book?

TA: Magic. When I see a páramo, a frailejón, I feel the magic of the universe. How is it possible that a tiny plant can capture water from the air, and that this same water is what we drink in the cities? It is the pure magic of creation. They are our water factories, our source of life. And we must protect them at all costs.

The title includes the figure of the “knight.” Who is that character for you? A symbol, a real presence, or a part of yourself?

TA: In essence, it is my brother, and also all the kidnapping victims of KM 18. My guide the first time I went to the páramo used to call the frailejones “The Knight of the Páramo.” Just as the frailejones are there, resisting, my brother was there too, among the páramos, resisting.

“A lot of anxiety, a lot of frustration, sometimes anger, and above all, pain. I thought a lot about that 12-year-old Tatiana and the whole imaginary world that was built around my brother’s kidnapping—how I should have never gone through that, nor should anyone”

Your writing has a very strong visual force. Do you think there is a relationship between your way of seeing—perhaps photographic or poetic—and the way you describe the landscape?

TA: I’m a lover of automatic writing: writing without thinking or filtering, pouring out everything you have inside without stopping until it all comes out. Surrealist artists used it to connect with the subconscious, and I used it to connect with my emotions. Perhaps photography helps me visualize those emotions; without realizing it at the time, I now see that both practices have been connected throughout my entire life.

Many times the páramo can represent solitude, resistance, or searching. What emotions were most present in you while writing this book?

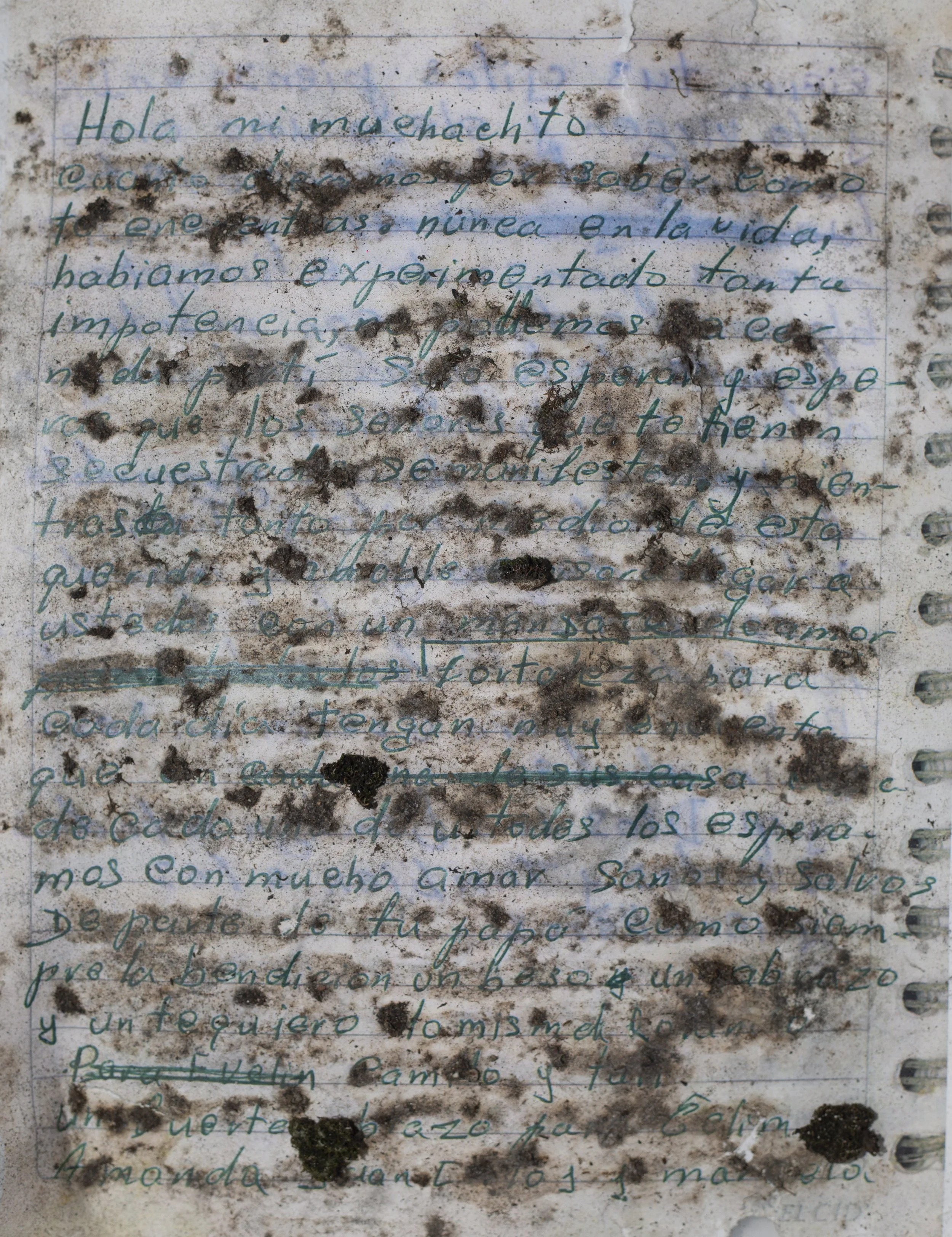

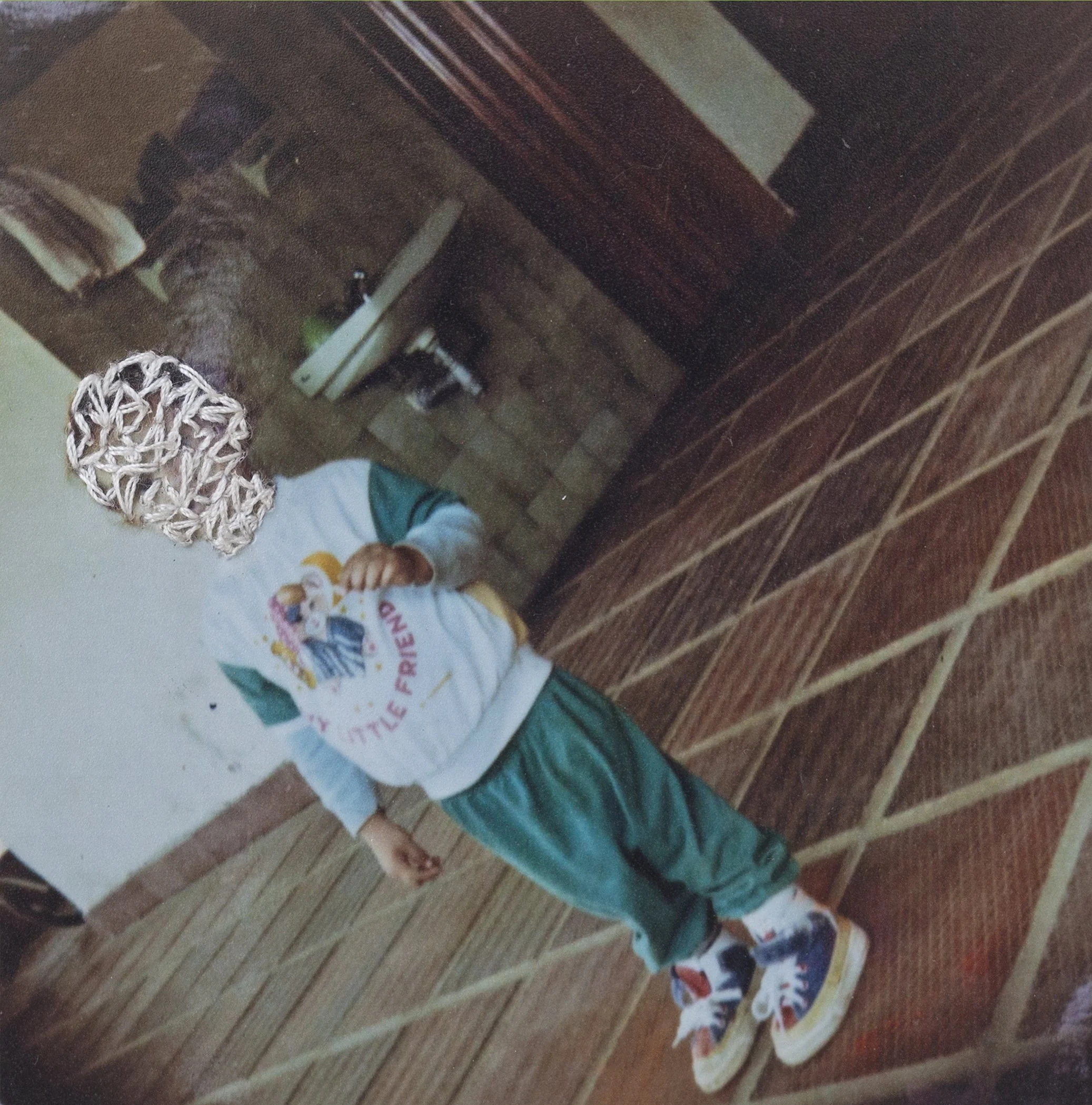

TA: A lot of anxiety, a lot of frustration, sometimes anger, and above all, pain. I thought a lot about that 12-year-old Tatiana and the whole imaginary world that was built around my brother’s kidnapping—how I should have never gone through that, nor should anyone.

That’s why I think my final act of creation was burning, submerging in water, embroidering, wrinkling the photos. I felt I needed to let all those negative emotions out and transform all that pain into art.

How was the writing process? Did it accompany you for a long time, or was it a piece written in a shorter, more impulsive moment?

TA: From the beginning, I knew I wanted to provide some context to accompany the photos. I knew I wanted to write and what I wanted to say, but I didn’t dare because texts can be more explicit, and that made me feel vulnerable.

Words allow people to enter my mind a little more. So I postponed it for a long time, until one day I let go of that fear and allowed myself to be guided entirely by my emotions. As a form of catharsis, and through tears, I poured out everything I had inside.

“ I hope they feel seen in the experiences we share. Something that surprises me is the universality of stories of conflict, not only in Colombia but around the world. Many times, these are stories we have silenced”

The language of the book feels ancestral and at the same time intimate. Was there any reading or voice that inspired you to build that atmosphere?

TA: Many works have inspired me—works that dialogue with memory and territory. I read Los ejércitos by Evelio Rosero and News of a Kidnapping by Gabriel García Márquez, and from what I imagined in those stories, I began creating my own images.

I’m fascinated by the way Carlos Ruiz Zafón describes Barcelona in his books, in such a way that I feel as if I’ve walked those same streets. That’s somewhat what I’m seeking: for moving through the pages of the book to feel like walking through the páramo.

Luis Carlos Tovar and his work Jardín de mi padre, Felipe Romero Beltrán with Magdalena, Clemencia Echeverri, and Doris Salcedo have been a great inspiration for creating from a place of awareness and pause—a language I also try to inhabit.

What do you hope the reader feels or discovers when they enter El caballero del páramo?

TA: I hope they feel seen in the experiences we share. Something that surprises me is the universality of stories of conflict, not only in Colombia but around the world. Many times, these are stories we have silenced—either because we have lived them intimately, out of fear, or because we chose not to confront them and simply move on.

I want people who carry unresolved pain to feel seen when they open this book.

What comes after El caballero del páramo? Are you exploring new territories—literary or personal—after this experience?

TA: I want to continue exploring from the intimate and the subconscious, telling stories that traverse us from north to south. I want what comes next to speak about women and their magic.

All rights reserveds © TATIANA ARISTIZÁBAL