JOANA TORO

All rights reserved © Joana Toro

Joana Toro is an artist and author whose work unfolds between image and intimate narrative. Her practice explores memory, identity, and personal bonds through a sensitive and contemporary lens, using the book as a space for reflection and experience. Rosalina is one of her most significant projects, where image and text engage in dialogue to construct a poetic work that invites the reader into an open and emotional reading.

What first led you to San Basilio de Palenque, and how was your first encounter with Doña Rosalina Cañates Pardo?

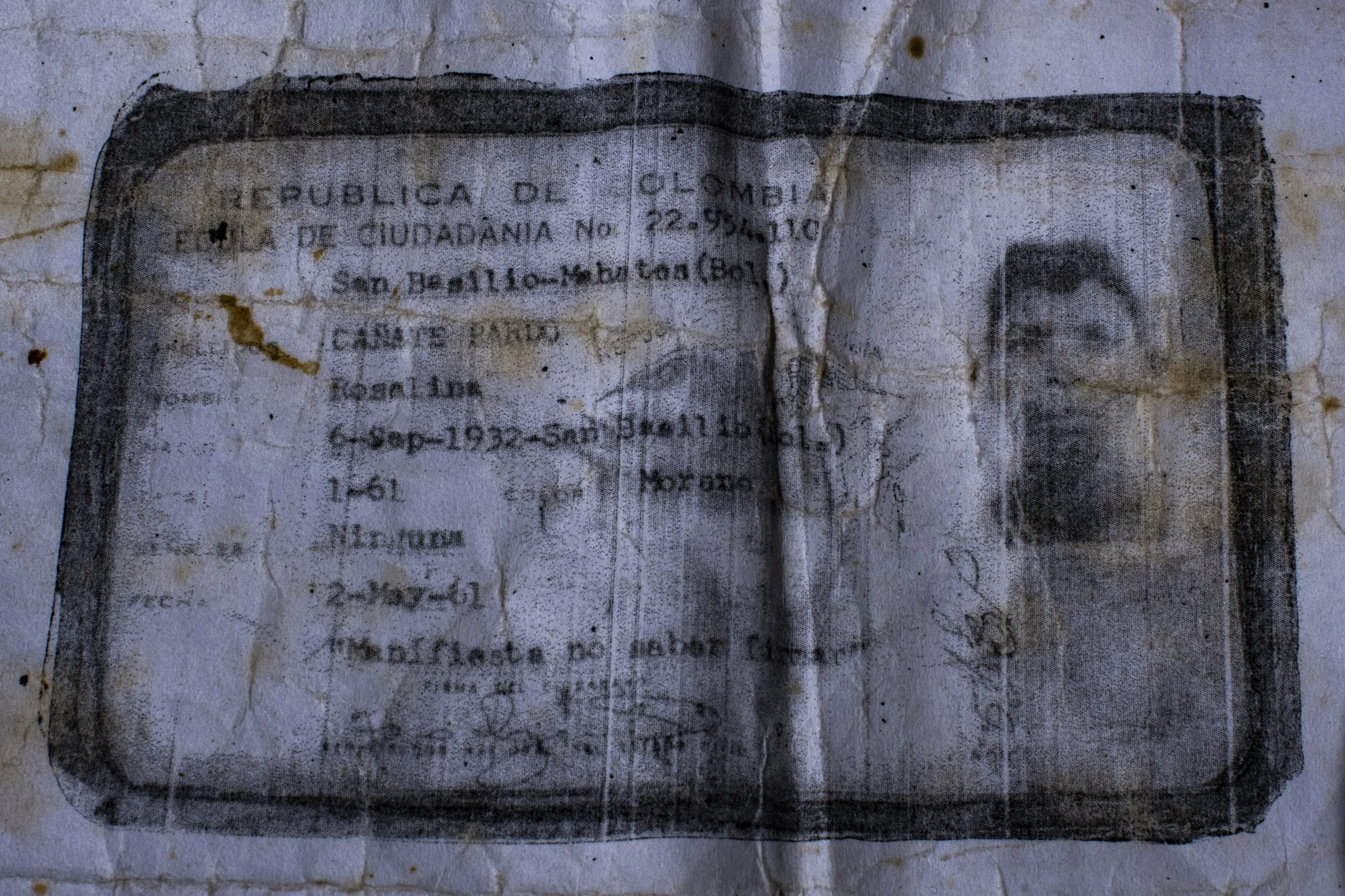

JT: My first encounter with Rosalina was seven years ago, in a context very similar to what any visitor experiences when arriving in San Basilio de Palenque. Guides usually take tourists to different plant healers to receive a blessing or santiguo, and those who participate typically leave a tribute as a gesture of gratitude. That day, after receiving the santiguo, I decided to stay a little longer than usual. I wanted to get to know Rosalina better.

You mention that you felt an unconscious connection to Africa. In what ways did this project help you recognize or reconnect with those roots within your mestizo identity?

JT: In 2009, I traveled to Palenque for the first time on a magazine assignment. It was a very brief trip, and the report focused on Lumbalú, a funerary ritual in which the people of Palenque bid farewell to their dead through songs and traditions, guiding their spirits toward the highest mountain in Africa. That same year, I also carried out a personal project on the Association of United Midwives of Buenaventura, where humanized childbirth, the use of plants, and African traditions are deeply intertwined.

Through these two bodies of work, I was able to clearly recognize the African influence that runs through Colombia and many countries in South America: we eat Africa, we dance Africa, and we speak Africa, even if we are not always aware of it. Working with Rosalina allowed me to reconnect with my rural roots, with the land, and with plants.

“Working with Rosalina allowed me to reconnect with my rural roots, with the land, and with plants”

Which aspects of Doña Rosalina’s knowledge of plants and traditional medicine do you feel best reflect the African legacy in Colombia?

JT: I believe she fully embodies that African legacy: in the way she lives, in how she inhabits and occupies her space. But it is above all in the moment when she sings the santiguos—those prayers where Christian and African syncretisms merge—that I feel Africa alive.

Africa is recognized in sound, in vibration, and in music, and in Rosalina that sonic memory continues to resonate with great strength.

Your text mentions the moon, plants, and natural cycles. What role do spirituality and time play in the visual construction of this work?

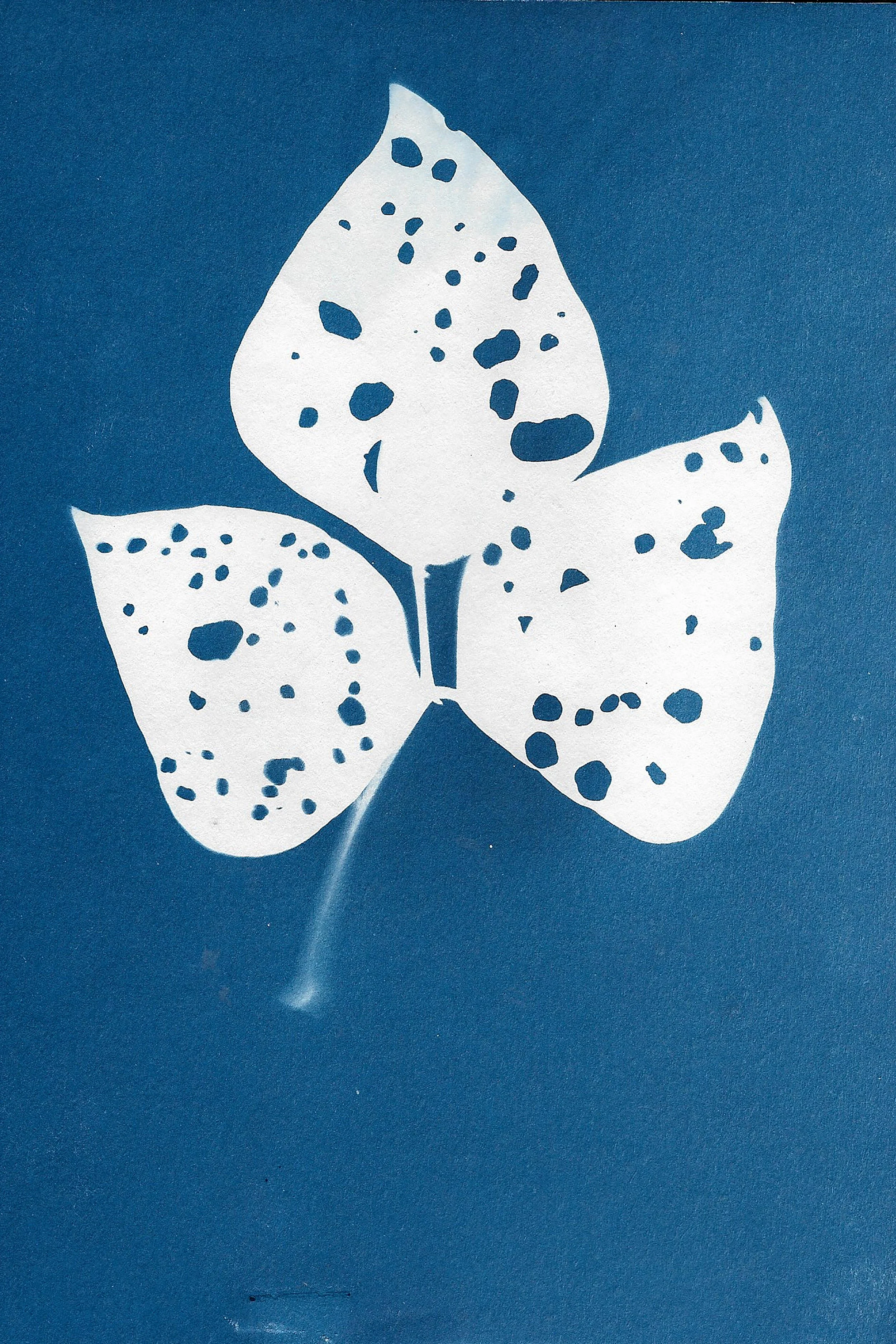

JT:Spirituality and time are the backbone of this work. In Palenque, natural cycles—the moon, plants, dawn—are not metaphors; they are living tools that organize daily life and healing practices. For Rosalina, healing is not an isolated act; it is a constant dialogue with nature and with spirits. Understanding this forced me to slow down and to look in a different way.

In my visual construction, time functions as a teacher. I do not work from immediacy; I work from slow observation, from being present. The light changes, the energy changes, the mountain changes, and I record those small movements. This temporality—more circular than linear—is what allows the spiritual to appear, even without directly photographing rituals.

Spirituality enters the project as an atmosphere, not as a spectacle. The moon marks the nights in Palenque; plants mark the days; and Rosalina’s voice, with her chants and santigües, creates a bridge between the visible and the invisible. My work attempts to accompany that rhythm, to respect it, and to translate it into images that do not explain, but rather listen.

Ultimately, this project is an exercise in synchronizing myself with that world: a world where healing, territory, and memory are in constant dialogue.

How did you build trust with Doña Rosalina and the community of Palenque in order to document her life and knowledge?

JT: Trust is built over time. In most of my projects, the more I live alongside the people I photograph, the more intimate the resulting images become. In the case of Palenque, being a community deeply proud of its culture, there is a generous openness toward those who arrive with a genuine interest in understanding the territory. In that sense, I was fortunate.

Even so, what truly makes the difference is the quality time I share with my subjects and the people I photograph; that dedication is essential for the work to have depth and truth.

“In my visual construction, time functions as a teacher. I do not work from immediacy; I work through slow observation, through being present. The light changes, the energy changes, the mountain changes, and I record those small movements. That temporality—more circular than linear—is what allows the spiritual to emerge, even without directly photographing rituals”

What challenges did you face when representing an ancestral tradition without falling into a folkloric or exoticizing gaze?

JT: It is difficult, because our minds have been colonized since birth. For that reason, as I mentioned earlier, I tried to work from a place of mindfulness: being observant, patient, and truly present within the territory.

I understand that for some viewers this kind of work may be read as an exoticizing gaze, and it is important to acknowledge that. I am not Black, nor do I live in Palenque; I am a mestiza woman of rural origin, although I grew up in the city.

My way of seeing emerges precisely from that rural lineage: from an intimate relationship with the land, from the knowledge passed down by my grandmothers, and from a deep respect for the communities I visit. I do not seek to appropriate a history that is not mine, but rather to accompany it, to learn from it, and to build images from listening and human connection, not from exoticism.

After so many years of visiting Palenque, how has your understanding of what it means to be Afro-descendant or mestiza in Colombia and in Latin America changed?

JT: I do not know exactly what it means to be Afro-descendant in deep identity terms, and I do not intend to speak from a place that is not mine. But as a mestiza woman, I can say that the land, plants, and the moon belong equally to all of us. With each passing day, as a society, we move further away from that nature, taking refuge instead in empty screens, filled with algorithms and plastic images.

I believe that being born into a rural culture—even though I later grew up in the city—allows me to see the world in a more grounded, more authentic way, or at least in a less materialistic one. In Latin America, both Black and mestiza people share deep roots tied to the land and to community. And I am convinced that when technology is no longer enough to sustain our emotional and spiritual lives, that knowledge will become fundamental.

The challenge is that we still live within a capitalist system that privileges disconnection, competition, and a worldview that breaks our ties with what is essential. My work seeks precisely to return to those places where the relationship with nature and with others remains a pillar of life.

All rights reserved © Joana Toro