BORIS MERCADO

All rights reserved ©Boris Mercado

My photos focus on people and their stories of migration, resistance, as well as the diversity and cultural richness of the world.

Boris Mercado is a visual artist and photographer, and the creator of Mitmaq Ediciones, an independent project focused on the production and circulation of artist-led publications. His work explores memory, identity, and the connections between the intimate and the collective, using photography and the archive as narrative tools.

From a sensitive and reflective perspective, his practice proposes a slower relationship with the image, where process and personal experience become central elements of his artistic work.

What inspired you to focus on the Santa Elisa building and its unique history?

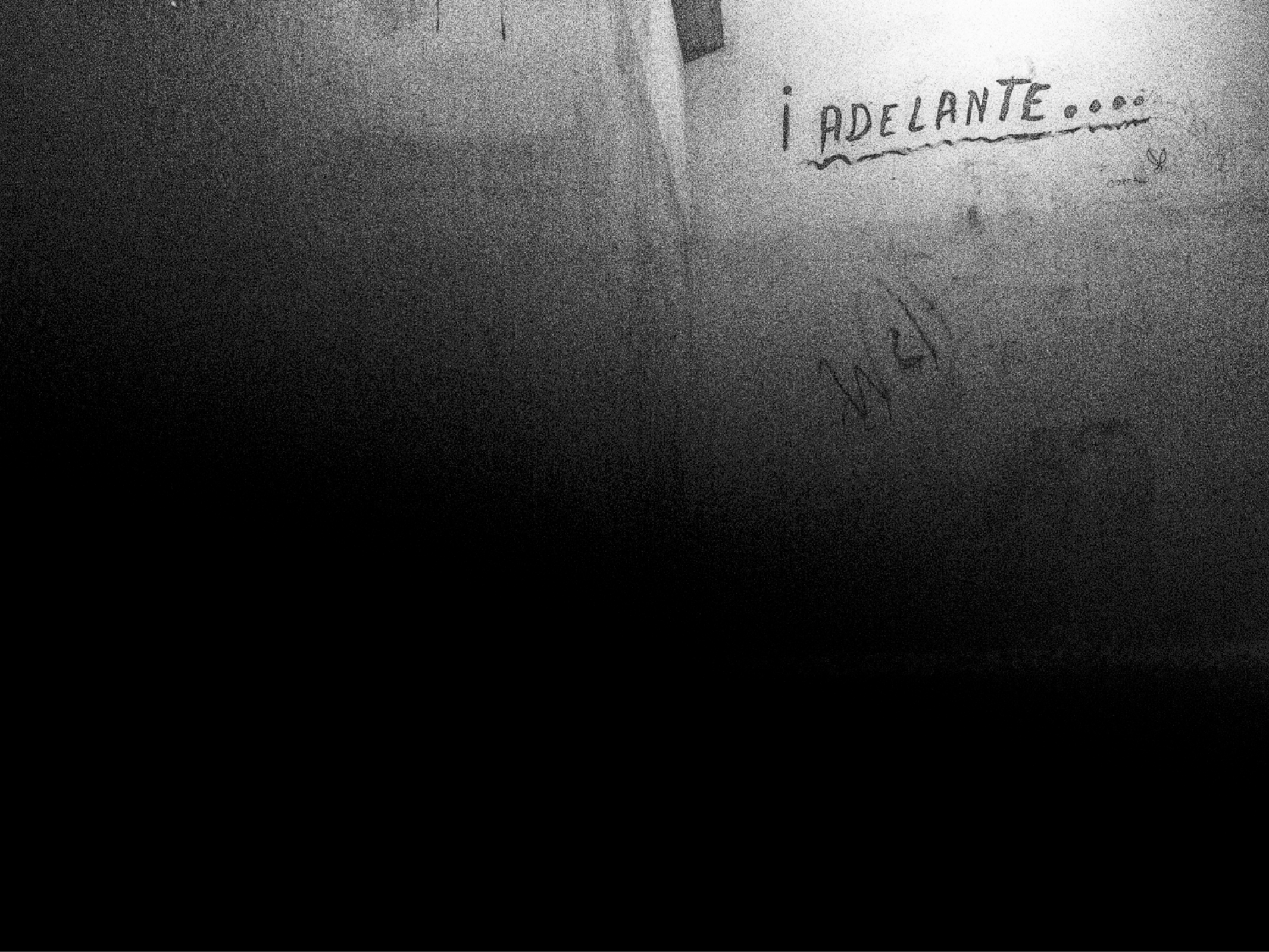

BM: When I first decided to go to Santa Elisa, I must have been around twenty-three or twenty-four years old, maybe a bit younger. One of the main things that inspired me was pure curiosity — I simply couldn’t imagine what kind of place could offer accommodation for two soles (the Peruvian currency), or about thirty euro cents a night. I also couldn’t picture what it would look like inside — a place where so many people lived together in a building that, from the outside, didn’t seem like a place anyone would live in at all. The façade looked more like a bank or a shopping mall, with its huge glass windows.

Another thing that made the experience possible, and meaningful, was the company I had. The warmth, the conversations, and the complicity of my best friend, Ollantay Sánchez, and my sister-like friend, Juana Gallegos, made it all feel more real and alive. They shared that same urge to understand what was really happening there — and that shared curiosity made all the difference.

How did you gain access and build trust with the residents living in such challenging conditions?

BM: At that time, we believed that having a parallel narrative would give us some kind of advantage, so we pretended to be immigrants in need of a place to stay for the night. That role allowed us to gain access during the first couple of visits to the building and its hostels. As we began meeting people inside, it’s worth mentioning that both Ollantay and Juana decided to step back and stop visiting the building. I, however, after understanding how the flow of entry worked, chose to stay for much longer — intermittently, over the course of about a year. It’s also important to note that I didn’t bring a camera at first. What I wanted, as I mentioned before, was simply to see what was happening and to feel what the place itself could transmit.

The trust that began to grow came gradually, through the small moments of connection I shared with the few people around me. These encounters helped me attune to the rhythms of those living there, and little by little, familiarity turned into trust. I developed a deeper bond with Walter, who appears in one of the photographs posing in front of the elevator that had become his home for many years — a space he had enclosed with wooden pallets. I also met Ezequiel, who doesn’t appear in the publication, but whose son does — the boy holding a toy gun.

Access came slowly, step by step. It was only during the final months that I decided to bring the camera and begin documenting certain things more deliberately. But even then, I focused mainly on capturing the emotions I felt at the time — the fear, the pounding in my chest, and the tightness in my throat that accompanied me every time I was there.

Could you describe the contrast you see between the interior of Santa Elisa and the city of Lima outside?

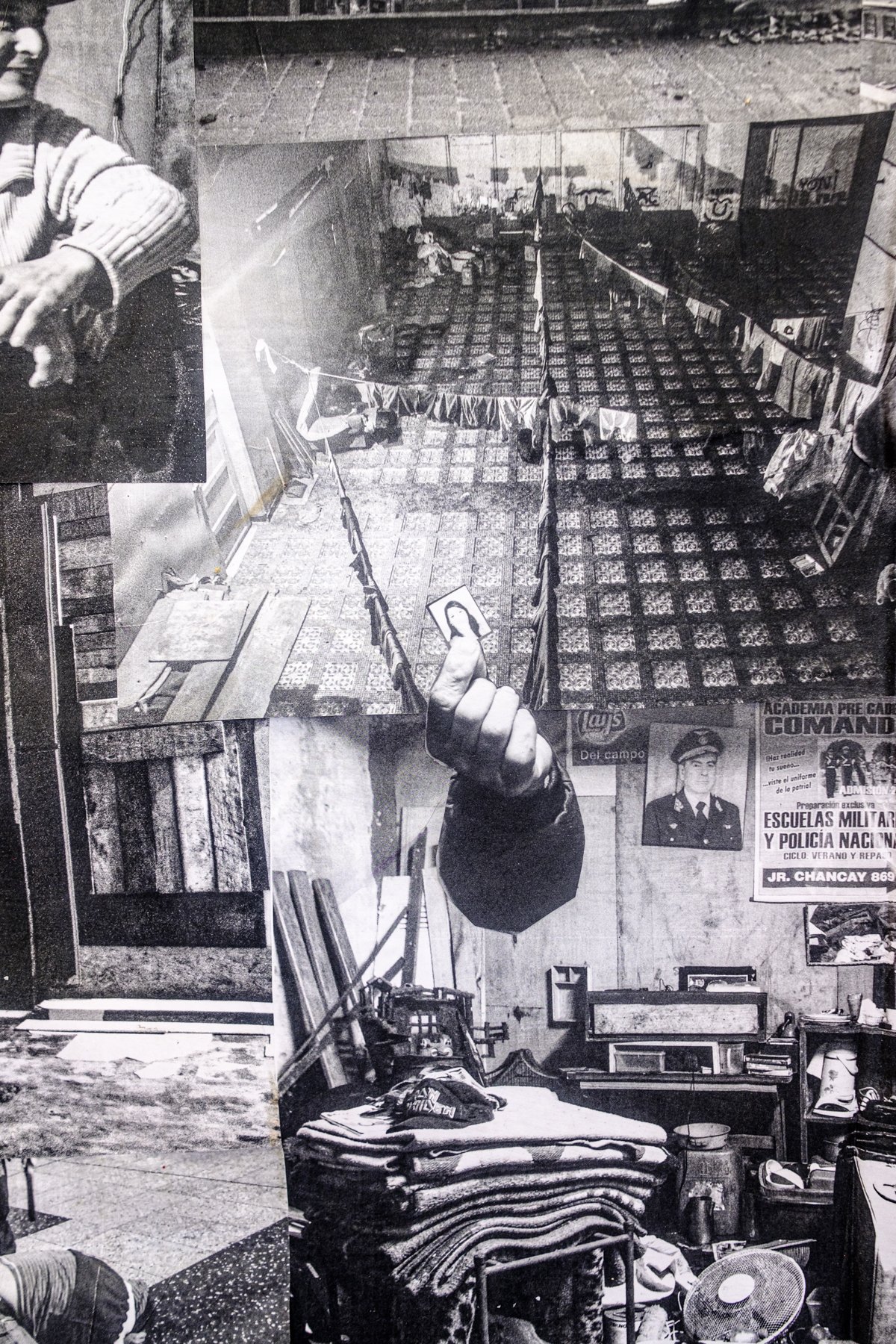

BM: Santa Elisa can be seen as a microcosm of Lima itself — a place built on contradictions, improvisation, and survival. Once a cooperative complex with banks, shops, and theaters, it now consists of makeshift housing and small hostels where residents pay rent to mafias that have taken control of the building. In that sense, it mirrors the broader reality of Lima today — a city where people must pay simply to live, to feel safe, and to avoid violence.

Peru is facing one of its worst security crises in decades. Violence and corruption have become everyday threats, and the government continues to repress those who protest. Within this context, Santa Elisa reflects those same contradictions, yet it also shelters people who strive to create a better life amid the chaos.

Inside the building, residents have made small efforts to bring order — setting curfews or trying to keep the space secure, even if these measures sometimes lead to tragic consequences, like a woman giving birth in a hallway. Despite everything, Santa Elisa stands as a living symbol of both fragility and resilience — a place shaped by control and neglect, but also by human will and community

What was your photographic approach to capturing both the environment and the people while respecting their dignity?

BM: I wouldn’t say I had a defined photographic approach at the time. Santa Elisa was my first real experience of connecting deeply with both a subject and the people I was photographing. It marked a shift from my earlier work as a photojournalist, where I often documented tragedies—collapses, murders, cases of sexual violence—without truly knowing the people involved or even remembering their names.

At Santa Elisa, everything changed. I began forming genuine bonds, spending long periods inside the building, sharing time and space with its residents. I tried to understand how a shared reality could feel so different for each of us.

That experience became a turning point—it showed me the kind of photography I wanted to pursue: one grounded in connection, respect, and presence.

What social or cultural messages do you hope viewers take away from this project?

BM:I believe it’s essential to understand our artistic practices within the contexts we inhabit. There’s a form of photographic extractivism in some documentary work—where little responsibility is taken for how images are made. Many photographers travel to Latin America or other regions of the Global South and, fascinated by the so-called “beauty” of difference, end up exoticizing what they see.

This project questions that approach. It seeks to use photography not as a tool of fascination, but as a means to expose and challenge the systems people live under. At the same time, it invites reflection on how we’ve normalized inequality and violence, urging us to become more conscious of how we look, whose gaze we share, and how our collective narratives are shaped.

Were there particular moments or images that were especially powerful or difficult to capture, and why?

BM: The photographs emerged quite organically. I wanted to capture the fear and tension I felt while being there. At first, I brought my camera only a few times, and I remember taking just one image—the main one—showing the building’s interior façade framed in red paint. That photograph set the tone for the entire series, guiding me toward a visual language that invites viewers to sense the texture, the roughness, and the noise within the images.

The hardest photograph to show is the one of the child holding a toy gun. Just days after I took it, his father, Ezequiel—who had hosted me in his son’s room during my final months at Santa Elisa—was shot and killed in the nearby neighborhood of Malambito. That loss made me realize the project had reached its end, not only for safety reasons but because the story itself had closed.

The true protagonist was always the building—how it reflects Lima’s contradictions and how it’s been transformed to shelter more than 250 families in what was once a bank, a theater, and an elevator hall. Those transformations, and the people I met like Ezequiel and Walter, made me feel both protected and connected. That’s why the later images became more figurative, more intimate.

All rights reserved ©Boris Mercado

Credits:

In collaboration for the exhibition Santa Elisa, Centre Cívic Golferichs, Barcelona, 2023.

Intervention: ft. Iván Arancibia (Mon)

Collage: ft. Desideria and Atoq Ramon