LUVIA LAZO

Can you briefly tell us who Luvia is?

L.L: A woman, curious, constantly asking many questions at once, who takes photos, writes, and usually goes to sell at the market with her mom on weekends.

In your series "KANITLOW," the hidden faces invite interpretation beyond individual identity. How does this choice influence the visual narrative you construct about memory and loss?

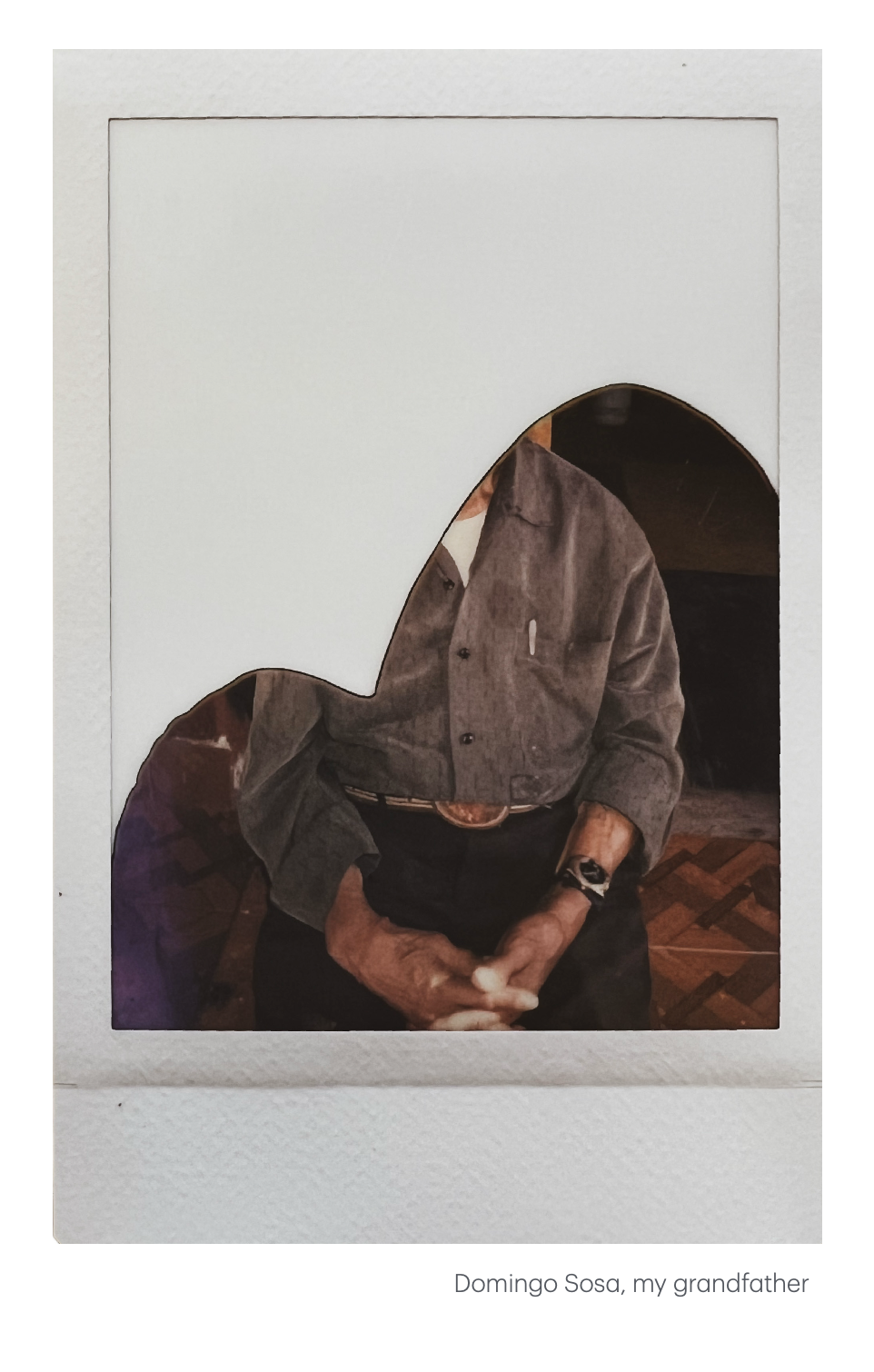

L.L: It has to do with language. The word itself marks the core of what I explore. It’s a word I heard from my grandfather; he said it to me, and I use it in other places almost with the same meaning. He lost my face, I lost his, and so the work became a record of faces that are lost. This absence is part of the whole, present in the photographs. With the “absence of the face,” there is also a broader, more universal reading. I don’t want to erase identity, but I like that gesture as a way to cover and protect those I portray.

“Mexico is no longer the same as in the times of Alvarez Bravo or Graciela. Many things have transformed, even from within—rituals, customs, ourselves. I’m interested in showing that those of us who belong to these “indigenous-origin”

You mentioned that your work seeks to document cultural resistance in the face of modernity. How do you balance the representation of traditions with contemporary transformations in your community?

L.L: No, my work does not aim to document cultural resistance. Rather, it seeks to document the process of transformation-resistance of identity. I am interested in studying, trying to understand, questioning, and photographing this moment that I live. Mexico is no longer the same as in the times of Alvarez Bravo or Graciela. Many things have transformed, even from within—rituals, customs, ourselves. I’m interested in showing that those of us who belong to these “indigenous-origin” territories also transform. Is there resistance? Probably a lot. Adaptation or reappropriation? Absolutely. I want to generate a conversation rather than give a single answer; I am merely a witness of a moment.

Your photographic process seems deeply connected to your emotions and personal experiences. How do you handle the intersection between the personal and the collective in your work?

L.L: Always. I dare to speak for many creatives: our drive comes from deep within. I don’t know if everyone is aware of it, but for me, it is always present. It’s both an advantage and a disadvantage because I need to be moved from deep inside; I need to connect with the topics I work on. Ideas come from secrets, anecdotes, and memories, almost always related to my family. It gives me great curiosity to understand ourselves and my relationships with them. When I connect everything to other things, I realize humanity is universal. We have repeated the same actions so many times, in others and in ourselves, across places. I don’t think anything is entirely individual; simply existing already involves others in our lives.

“Objects and textiles are very present where I live. My work is imbued with these elements because they are part of daily life”

In your portraits, objects and textiles play a prominent role. What significance do these elements have in constructing identity and memory in your images?

L.L: Objects and textiles are very present where I live. My work is imbued with these elements because they are part of daily life: glimpses here and there, women wearing woven pieces mixed with imported fabrics, my mom wearing her apron with printed Chinese silk flowers, baskets full of plastic containers, wooden and metal objects, native flowers alongside introduced species, Catholic rituals and ghosts of pre-Hispanic rituals. It’s a mix. I portray this moment more to leave a trace than to make a judgment.

During your recent visit to New York, you mentioned starting a new photographic project focusing on twin migrants from Oaxaca who now live in New Jersey. Could you share how the idea to document their lives arose and what aspects of their migratory experience motivated you?

L.L: The idea was never to photograph them because of their migration. We connected because our parents did the same work—meat processing. I wanted to understand how other women relate to this difficult, harsh work involving animals, death, blood, flies, and dirt. Yet they always seemed so full of tenderness and curious about the world. That’s how it began: as a search for myself in them. Their life choices led me to follow them to New York. It took me two years to see them again, during a complex political moment, when I already knew I wanted to follow their story.

“Polaroid allowed me to be present. Now that I see the photos in Oaxaca, there are only those photos, only that memory. I liked playing with double exposures—they are twins, and I liked that they could become four, then one representing both, then two—like a magic trick for me and the viewer”

Can you tell us about “ña’a to’o lili”? What does it mean and how did the name come about for this project?

L.L: It means “foreigner, mestiza.” When I arrived in my friends’ community, I was a “ña’a to’o lili.” Everyone knew me that way, even though I tried to explain I wasn’t mestiza but Zapotec. I couldn’t remove the layer of foreignness. When they arrived in New York, that sense of belonging shifted. At that moment, they too became “ña’a to’o lilis.” The three of us were in that position in this country, and I photograph them from that perspective of equality—two women dreaming in a place different from where they belong.

“When I arrived in my friends’ community, I was a “ña’a to’o lili.” Everyone knew me that way, even though I tried to explain I wasn’t mestiza but Zapotec. I couldn’t remove the layer of foreignnes”

For this project, you are using instant photography as a new approach. What drew you to this medium, and how do you think it influences the visual narrative of the story?

L.L: I decided on the format mid-process. I was nervous about digital data and wanted to be fully present. Digital allows for many images, many chances. I wanted just one—the one that would appear. Polaroid allowed me to be present. Now that I see the photos in Oaxaca, there are only those photos, only that memory. I liked playing with double exposures—they are twins, and I liked that they could become four, then one representing both, then two—like a magic trick for me and the viewer. There are no metadata, only memories of our walks and moments. No files to edit, no control. I come from a series with editorial-style photos, controlled backgrounds, perfect framing. Polaroid freed me from that control.

Finally, how would you like your work to be perceived by future generations in your community and by external audiences? What legacy do you hope to leave through your images?

L.L: I would like my work to spark conversations. I want viewers to feel something—not just beautiful things, but perhaps discomfort, disagreement, nostalgia, or sadness. I want young people to ask why a woman at that time saw these things, to question my perspective, to challenge it, and maybe change theirs. Much of what I photograph is shaped by my knowledge, beliefs, and experiences; it’s personal, not meant to represent anyone else. I want it to awaken curiosity and reflection.

All rights reserved ©Luvia Lazo